Faceless and still, it would be easy at first glance to miss the tiny tube feet and mistake a sunflower seastar as part of the rocks they quietly rest upon.

But these are social creatures and can move at 40 inches per minute. They have been nearly wiped out in California, by sea star wasting disease.

“Of all the sea stars, the sunflower star was hit the hardest,” said Jason Hodin, senior scientist at the University of Washington Friday Harbor Marine Laboratories.

Hodin’s scientific career had early roots in the FH Marine labs where he was a student in the 1990s. He has been researching sunflower sea stars since 2019 after the Nature Conservancy contacted him about a sunflower star reintroduction project. The species typically can be found in the intertidal and subtidal zones from Baja Mexico to the Aleutian Islands in Alaska. In California, however, there are very few left.

“[Sunflower stars] are almost completely gone from California. They are functionally extinct,” he said.

Functionally extinct means there are not enough left to reproduce. At about the same time sunflower stars declined, bull kelp also began disappearing. Scientists like Hodin realized there was a lot about these animals that humans do not know, knowledge gaps regarding entire aspects of their lifecycle.

“It is amazing how little work has been done on [Sunflower star] larva, and there have not been a lot of publications on their lifecycle,” Hodin said.

If reintroduction is to occur, there needs to be a deeper understanding of Sunflower stars, sea star wasting disease and the impacts of ocean temperatures. The “Blob,” a mass of unusually warm ocean temperatures off the coast of California, Oregon and Washington a few years ago, could also have contributed to species decline. “It all may contribute and in California we are still seeing the effects,” Hodin said. When considering reintroduction, taking a good look at how the sunflower stars handle warmer temperatures is key.

The causes of Sea star wasting disease are unknown, according to Hodin, although it appears to be an organism that reproduces similarly to a virus. Bacteria, fungi or a combination are also possibilities. Symptoms include white lesions, tissue decay, body fragmentation and death. There is work being done in a lab in Olympia, Washington to find the answers, according to Hodin.

If it is a virus spread by close contact it would explain why Sunflower stars were hard hit. Looking at two and three-year-old stars in Hodin’s lab, all are knit closely together, arms touching.

“They are very gregarious animals and touch each other a lot. When we introduce a new one they have a meet and greet,” Hodin said. “They are not wearing masks and there is no vaccine,” he added wryly.

In the Friday Harbor lab’s Sunflower star nursery, the tiny stars are barely visible. At this stage, they only have five arms. As they grow larger more arms appear. The young starfish feed off baby urchins, which Hodin and his team have learned to raise. They are also fed what Hodin calls Oyster flour. The recipe includes crushed oyster shells with baby oysters on each one. Hodin and his team have discovered the young stars are voracious. One of the many things researchers are learning as they fill in the lifecycle gaps is that younger stars may consume five to ten times more urchins on a daily basis than adult stars. If that is correct, a lack of young stars could play a role in increased urchins. Urchins feed on kelp, so an abundance of urchins could damage kelp forests.

The researchers are also discovering eelgrass plays a big role in the young star’s lives as well. Like kelp, eelgrass has also declined in some areas. To find out more about the connection between the two species, the team has been collaborating with local eelgrass specialists.

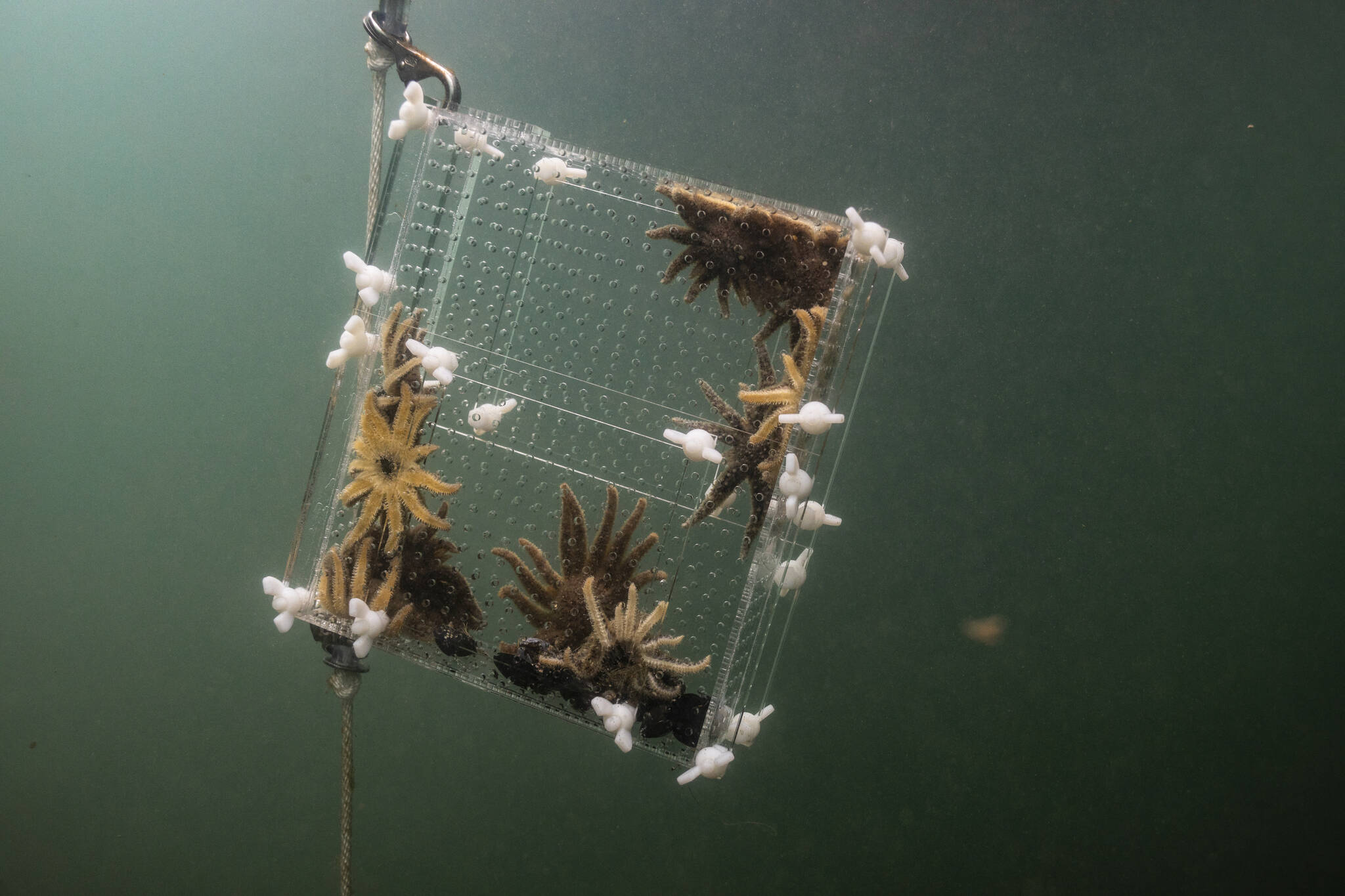

To gain insight into how the stars do in the wild, Hodin and his team have several stars in plexiglass cages throughout the San Juans, Unfortunately, one of those cages went missing after July 31. Any information can be emailed to labrador@uw.edu.

With so much more to learn, the lab could easily become a larger operation. Between water filtration, raising food for the stars and habitat for the stars themselves, they could easily fill a warehouse-sized building.

To help fund the project a donation site has been created through the University of Washington. To donate go to https://together.uw.edu/Campaign/seastars. The site has helped out when equipment has broken, or other unexpected costs arose.

“The Nature Conservancy has been visionary by supporting this work and has been carrying out incredible efforts in California, including working with a kelp recovery team. They had a lot of trust in me, and they are working toward real solutions and it has been amazing,” Hodin said.