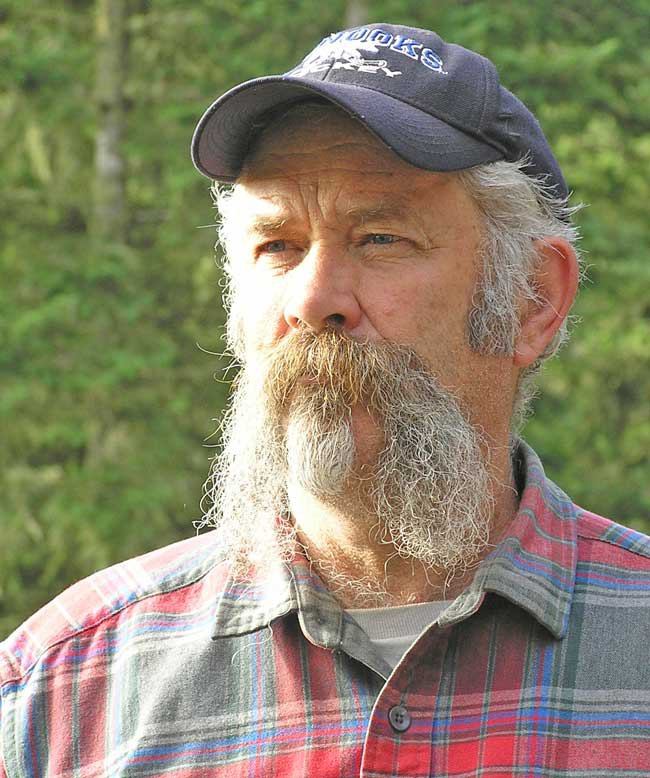

by Steve Ulvi

Most of us find indescribable solace in the mysteries of the natural world.

We seek rejuvenation in the suspension of human clock-time in favor of natural sensory time. Time-out rekindles our sense of humility and respect for the larger community of life to which we are linked, if only for a moment, a sunset, a week or perhaps a lifetime.

Immersion experiences in wild places – “breaking the suction of town” – can run the gamut: tranquil moments, exhausting climbs, wading swollen creeks, the endless play of light and clouds, pitch darkness, hunkering under a tarp in a downpour, senses heightened and evidence all around of the ephemeral nature of life.

Our reverie is sometimes overcome by imaginary and very real fears that release hard-wired reptilian brainstem reactions.

Let’s pause in our harried lives and celebrate the 50-year anniversary of a unique social construct: The Wilderness Act of 1964, a profound idea born in the crucible of American hyper-development and social upheaval in the post-WWII boom years. Places preserving solitude, natural sounds and a tactile sense of the “forest primeval” were disappearing as quickly as Bob Marshall’s prosaic “snow bank in August.”

My first serious brush with designated Wilderness came in a week-long summer backpacking hump through the Desolation Wilderness in the Sierras.

Shouldering a heavy borrowed pack, a short fishing pole, plenty of granola and brown rice, haiku and Gary Snyder paperbacks, my four outdoorsy teenage pals and I crossed the high Sierras under our own power. We were exuberant souls stripped bare by the awesome powers of the natural world.

Like the billowing afternoon thunderstorms that slammed our granite world that week, my life’s course was profoundly altered by flashes of hope and energized aspirations. I badly needed the confidence of primitive self-reliance. I knew that I had to turn the clock back to a simpler time and live counter to mainstream culture.

After years of backpacking all over the West, while living among the “madding crowd,” an insatiable childhood itch landed my companions and me in Interior Alaska in 1974 to hand-build cabins and live on the fabled Yukon River.

Enthralling tales of grit and perseverance from the pages of Service, London and others leapt into multi-dimensional reality by lamp light. We experienced a winter-dominant landscape of unimaginably vast taiga, emitting the barely discernible deep thrum of primeval quiet.

My foolish notions and fantasies faded. There, small outposts of humanity are surrounded by vast wild landscapes, which were the opposite of the proportion of the “civilization” of my upbringing.

The Wilderness Act was the direct result of a key association of America’s most forward-thinking adventurers and advocates for voiceless nature who formed the Wilderness Society. They understood the future of rampant, front-country development, uncertainty in industrial roading and logging within public parks and forests, and fought to preserve some measure of wildness.

The key definition for designated Wilderness, which only Congress would forever be able to designate or take away, is elegantly simple: “A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain”.

Wilderness areas (some 750 areas in 44 states) are a unique “geography of hope” within the American landscape. We now know that most areas are smallish islands of scenic, high elevation “rock and ice” limited in biological richness and diversity. This is not the case in the huge and uniquely Alaskan areas created in 1980.

The complex histories of millennia of human use and occupation there still unfolds along side modern recreational pursuits. There, the immutable laws of mountains, glacier ice, rushing rivers, endless forest, lashing storms, dangerous wildlife and gritty physical challenges reign.

Danger makes you dig deep.

I have felt the dank breathe of the Pleistocene raising the hairs on my neck thousands of times in the wilds of the West and Alaska. I trust that you too feel deeply indebted to wild places.

Steve Ulvi retired from the National Park Service in interior Alaska in 2006. He lives on San Juan Island.