Marshall Howard Bliss died late on Tuesday, April 16, at the Longhouse on Orcas Island.

He was born Nov. 26, 1949, in Gooding, Idaho, and spent his early years there, in Bliss, Idaho, and in Florida. If asked where he was from, though, he might have answered, “Well, I grew up in Viet Nam … ” His mother, Rose Marie Myers, was Irish. His father, Don B. Bliss, was Nez Perce Indian and a direct descendant of the legendary Chief Joseph (Hinmatoowyalahtqit).

A few years before Marshall was born, Don fell hundreds of feet down a mine shaft, breaking nearly every bone in his body and barely surviving. Marshall, too, was a survivor; beginning with a lonely and often violent childhood.

He lied about his age and enlisted in the Army at 17. He did his basic training at Fort Lewis and became a medic on a “dust off crew,” one of four men on an unarmed helicopter that would fly to the frontlines and beyond to rescue wounded soldiers. Marshall wasn’t one to casually share the experiences he had in Vietnam, but from what can be gathered it is safe to say that he faced the horrors of battle with great courage and honor, and came home with his share of ghosts.

After finishing two tours, he was discharged, and on his way home he deplaned in the Philippines, doubting his readiness to return to civilian life in the United States. Eventually he found refuge in Wrangell, Alaska, where he worked in restaurants, a sawmill, as a treatment counselor and a fishing guide.

He lived and played hard. Most importantly, perhaps, he met a Lakota medicine man who opened the door into the traditions and ceremonies that Marshall pursued for the rest of his life.

Marshall moved to Orcas in 1989, and over three decades wove himself into the fabric of many lives and families here. Diving into the phosphorescence in Olga, leading sweat lodge ceremonies all over the island, hunting elk in Eastern Washington with Tim Ordwing, fishing the Thompson River in Montana with the Doty clan, mowing the lawn in a lightning storm (and healing the wounds of war) at the Willis-Fox homestead; these are the details of a legacy of healing and laughter and sacred time that Marshall shared with loved ones on Orcas.

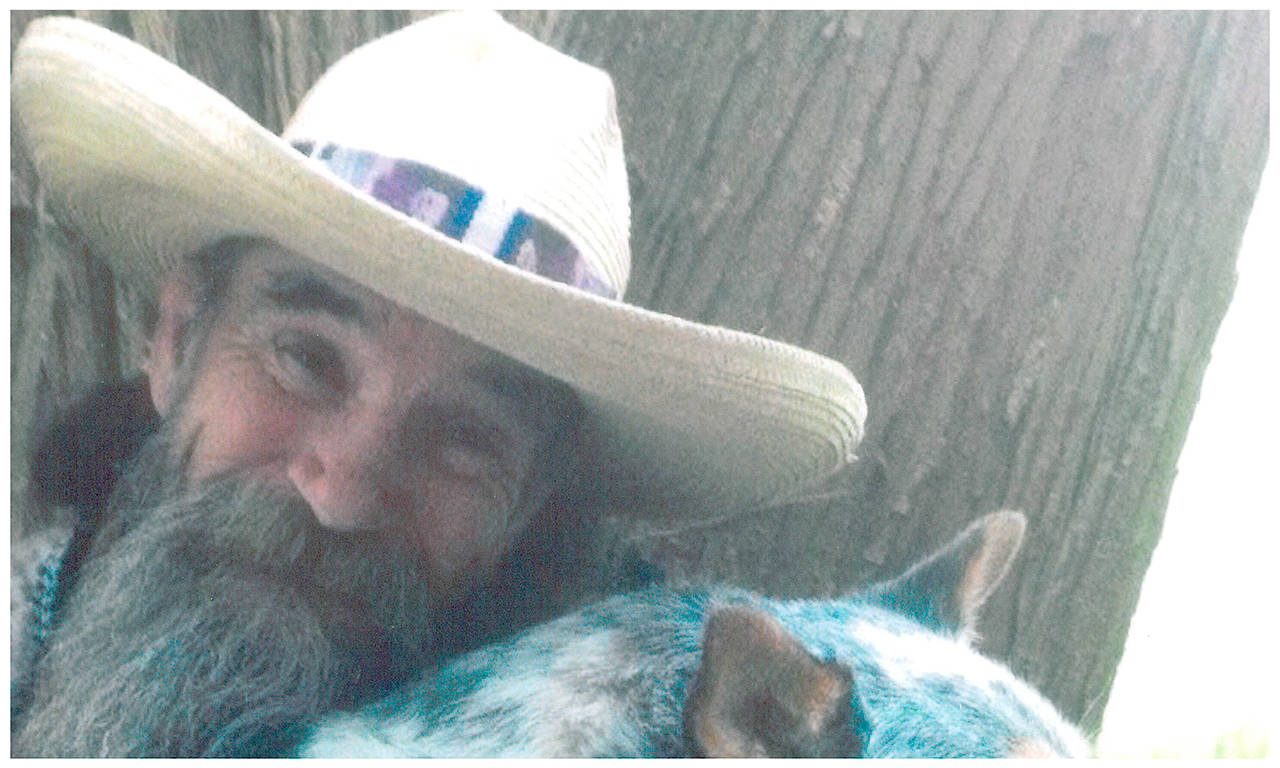

The last precious gift that Marshall had to give was his death; a gift given to the circle of friends who came to his side in his final days to nurse and give solace and thanks. They know who they are. Marshall was a Sundancer and pipe carrier, a poet and artist, a gold miner and hunter, a logger and a wedding officiant. He was a dog lover and a clam digger. He was a student of Wallace Black Elk and adopted grandson of Pete Catches. The Lakota name given to him translated as “dependable.” He was also fearless, loyal, ornery and funny as hell. He was preceded in death by his beloved dog Smokey. He is survived by his former wife Marcy Benham, and many friends.