A staggering 74 percent of bulkheads, or armoring, constructed along the shorelines of San Juan County over the last 10 years are not permitted, according to a recent study conducted by Friends of the San Juans.

“This isn’t just happening here, this is what people are finding in other areas across Washington as well,” said Tina Whitman, Science Director for Friends, a local non-profit that has been researching forage fish habitat over the last 20 years.

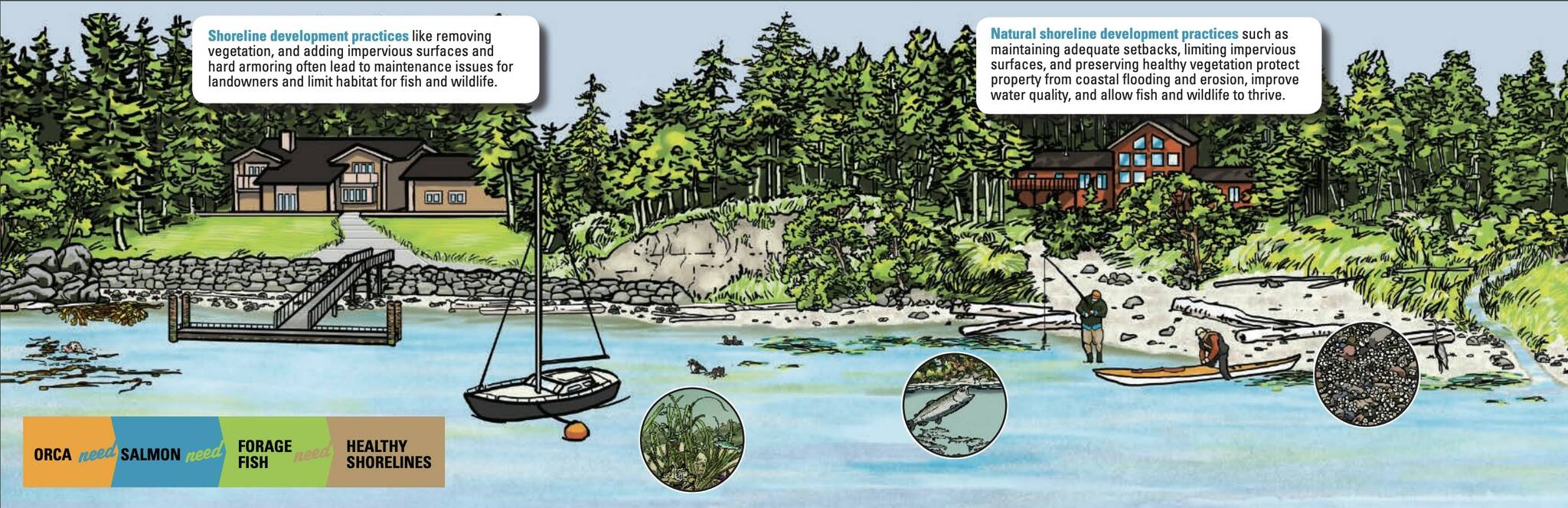

During a public workshop on Dec. 6, Whitman defined armoring as a wall along the shoreline consisting of concrete, rock or wood with the idea of stopping erosion. Armoring can be built in the high tide zone or constructed lower, directly on the beach.

Occasionally there are no alternatives to armoring. For example, a house may be in danger of falling into the sea. Whitman pointed out that often property owners install sea walls simply for landscaping purposes, not realizing the detrimental effects on beaches and the wildlife that depends on them.

“Natural erosion processes are important for maintaining beaches,” Curt Hart, the Washington State Department of Ecology’s communications manager said. “Hard armoring can cut off the supply of sediment needed to maintain our beaches and the habitat they provide, and worsen erosion on nearby beaches. This harms the delicate ecological balance that ensures the survival of salmon, shellfish, and other native species.”

Whitman explained that less wood, seaweed and other organic material accumulate on beaches with armoring. Insects feed on the organic matter that naturally builds up on beaches. A decrease in seaweed and logs means fewer invertebrates. No bugs along the shore mean no food for juvenile salmon. Studies have shown, according to Whitman, that juvenile salmon along armored coastlines have less food in their stomachs than those along unarmored coastlines.

Other impacts include a coarser substrate, which is unsuitable for forage fish spawning, reduction in native beach vegetation, steeper beach profile and less resilient beaches for sea level rise.

These well-known and well-documented impacts are precisely why constructing armoring requires two permits: one from county agencies and a hydraulic permit issued by the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife.

While 74 percent of armoring in San Juan County is unpermitted, an additional 17 percent either had only one of the required permits or landowners obtained after-the-fact permits. Monitoring after the armoring is complete is also required, and after a detailed public records request, Friends staff found there was little evidence of follow-up inspections.

“I wasn’t surprised by those findings,” said David Williams, Director of San Juan County Community Development.

Williams became joined the department in 2021, after the study’s end date. He explained that Community Development is fully staffed for the first time in years. An additional code enforcement officer will be coming aboard next year. The new employee, according to Williams, will spend their time split half and half between enforcement and working in the Environmental Stewardship Department.

“They will spend their time one hundred percent on the environment,” he said. Once that individual is hired, code enforcement will be in a better position to take on inspections. “For every permit, we issue, it’s critical to get those inspections done.”

When asked if ecology was surprised by the lack of permits and inspections, Hart responded, “We haven’t evaluated the report findings in-depth but we agree with the report’s conclusion that ‘much more effort is needed to accurately track on-the-ground conditions to adequately protect marine shorelines ensuring compliance with existing regulations.”

Whitman said there is currently little incentive to get a permit, especially considering the process is long and costly.

Williams added that should code enforcement get involved, tens of thousands of dollars in fines can accumulate, and civil or criminal actions can be taken against the landowner. The state can also levy fines and civil or criminal penalties. Contractors can face fines as well for taking on unpermitted projects.

“I would rather help people do things the right way than get code enforcement involved,” Williams said, encouraging the public to work with Community Development staff to see what is possible with their site.

Through the Friends study, it also became apparent that the data state and county officials look at when permitting new armoring is not accurate as they are looking at what is on record and not what is actually on the ground. Agencies may approve a project assuming there is no other armoring in the vicinity when that might not be accurate.

There was no evidence of any requirement for mitigation of forage fish habitat loss in the permits Friends staff looked at. Almost all new armoring permits seemed to have a cookie-cutter element to them with frequent errors like landowners’ names being wrong and almost always blanket no-impact statements being issued, without any backup evidence or information.

State data also reflects more armoring being removed that being installed, Whitman said. The Friends study shows the opposite.

Restoration, Whitman continued, has been touted as the answer, with billions of dollars being thrown at it. She says prevention is an even better solution: refraining from building unnecessary or ill-constructed armoring in the first place is ideal.

“It takes a lot of work to put things in and take them out. It cost millions of dollars. Instead, just don’t put it in in the first place,” she said, reiterating that some armoring is necessary, and Friends is not against all armoring. “We just need to do a much better job with tracking and inspection.”

According to Williams, the county is in the process of conducting its own cumulative effects study, required by the state every four years. The study is similar to the Friends report in that it is an on-the-ground effort to see what development is taking place on local beaches. Williams said he expects the results by late summer.

“When people see things occurring on the shoreline. Please call us,” he said. “The sooner we hear, the sooner we can respond.”

WDFW is also collecting information to improve the performance of both DFW and the permittee. They released a one-year progress report in 2015 and a five-year progress report in 2019. They can be found at https://wdfw.wa.gov/publications/01746 . If you encounter a potential hydraulic violation, you can report it on WDFW’s website at wdfw.wa.gov/license/environmental/hpa/hpacompliance.