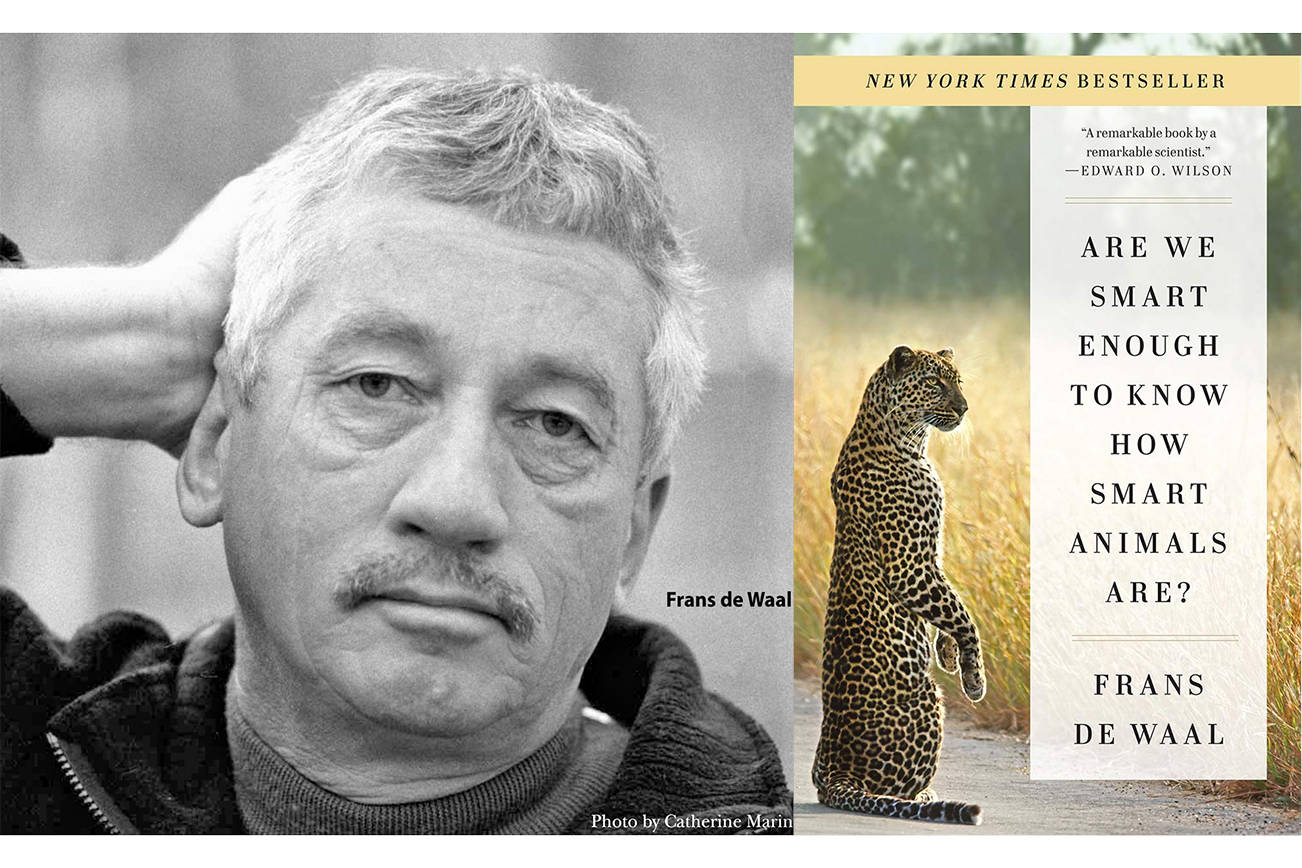

For more than four decades, Frans de Waal has studied primates to discover their intellectual capabilities. On Monday, Oct. 1, de Waal spoke about both how smart animals really are and their emotional intelligence to an audience gathered at the Sea View Theatre. The lecture was sponsored by the SeaDoc Society.

“I think animal emotions are completely underestimated and very highly developed,” he said. “Certainly in all the mammals but also in the birds.”

Since the mid-1970s, when de Waal earned his doctorate in biology, he has tested the intellect of a variety of animals. Early on in his studies, de Waal said that many people were opposed to animal intelligence testing, assuming that they were not capable of thoughts and feelings. Each test has to be different depending on the animal, he explained.

“We have gone through a long, dark period of about one century in which we were not allowed to talk about animal intelligence. … We live in a time which there is a lot more interest in the cognitive capacities of animals,” de Waal said. “Each species has its own way of dealing with the world. … So you need to do species-appropriate testing. That’s a very difficult proposition.”

De Waal shared a video of cognitive and emotional tests performed on chimpanzees, elephants, birds and gorillas. One of the first scientists to say that animals think was psychologist Wolfgang Köhler. Before that, there were two schools of thought on why animals acted a certain way: behaviorism and cognitive psychology.

“Animals can think things through and come up with a solution,” de Waal said. “This is something that the behaviorists did not want to hear.”

Videos shown by de Waal during his lecture included a 1930 recording wherein two chimpanzees had to cooperate to drag a box of food to them. Even when one of the two test subjects had already eaten, the full chimpanzee aided – albeit reluctantly – the other in dragging the box over. De Waal said this is an example of reciprocity and empathy.

“Reciprocity is very highly developed in chimps,” de Waal said. “They do each other favors all the time.”

Elephants and orcas have also been observed working with each other toward a common goal.

“There must be some very sophisticated communication going on to line up like this and do that together,” de Waal said of killer whales off the shore of New Zealand that team up to knock seals off ice sheets.

Chimpanzees have shown the ability to console each other when one of them is injured or scared. De Waal also referenced the 17 days that grieving mother orca J35 carried her deceased calf with her through the waters of the Salish Sea.

“You get that, of course, only when there is an attachment – grieving or mourning. If there is not attachment, there’s no reason to have this kind of phenomenon going on,” de Waal said. “I do think that grieving is involved. I have no reason to assume based on the behavior and the circumstances that there are not these kind of emotions involved in the process.”

For more information about de Waal, visit http://www.yerkes.emory.edu/research/divisions/developmental_cognitive_neuroscience/dewaal_frans.html.