Deer Harbor’s Cayou Lagoon is slowly silting up, choking under a thick layer of mud.

Bob and Meg Connor, who own a 140-acre estate bordering the lagoon, remember playing “Pooh sticks” with their children off the Channel Road bridge in the 1970’s, dropping bits of wood off the upstream side.

“We saw millions of fish going into the lagoon,” said Bob. “There used to be oysters, crabs.” Now, he says, people are incredulous at these stories; there are few signs of life in the murky depths.

Historical documents and old islanders say the estuary was once a deep and vibrant “nursery of the sea” nurturing spawning fish and shellfish, sheltering migratory birds and feeding numerous other wildlife.

Now, locals call its muddy, shallow waters “the slough.” Kwiaht director Russel Barsh calls it “one of the most damaged marine habitats in the county.”

The Connors, in conjunction with nonprofit organizations People for Puget Sound and Kwiaht, neighbor Ken Brown, and countless other volunteers, are hoping – and working – to turn the tide for Cayou Lagoon and restore the estuary to its original state.

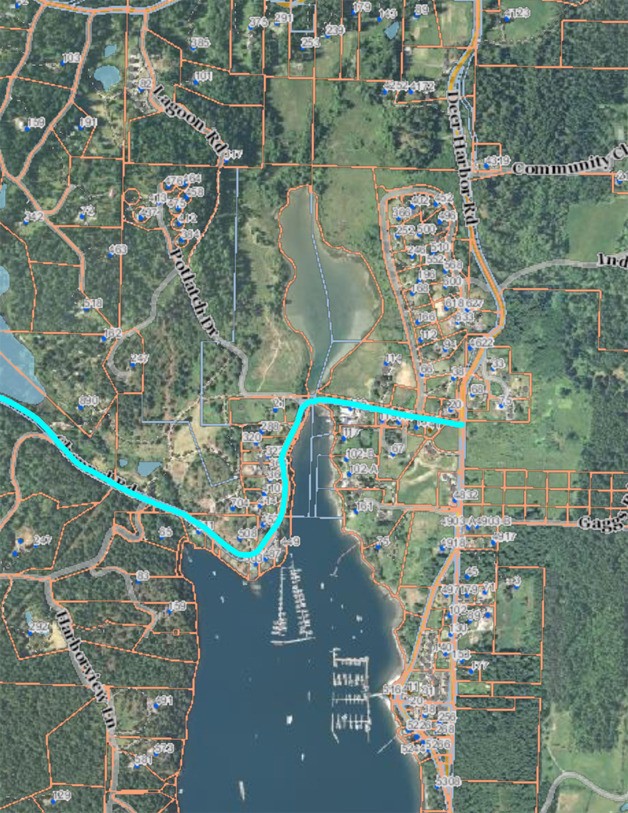

Historical documents indicate that in the 1800’s the estuary was home to native Coho salmon, navigable by boat, and the site of a flourishing native American fish trap. The estuary includes the two tributary creeks, the lagoon, the lagoon’s outlet channel under the Channel Road bridge, and the inner harbor. Diary records by pioneer natural history researcher

Caleb Kennerly mention that in 1859 he traveled up into the lagoon’s main tributary, Fish Trap Creek, by boat, said Barsh.

Today the lagoon is about five feet deep and on its way to becoming a “mud flat,” home to mud snails and tube worms. When geomorphologist Jim Johannessen and Barsh tested the depth recently, an entire seven-foot steel probe slid straight down into the mud and vanished. “[The mud] could easily be 10 to 15 feet deep,” said Barsh. “Nothing is going to live in that except bacteria.” The aquatic life remaining is concentrated around the bridge, where oxygenated salt water laps against the brackish lagoon, allowing barnacles, chitons and small crabs to flourish. While the area is home to many birds, Kwiaht researchers Charlie Behnke and Amanda Wedow are finding that very few are fish-eating species.

But why?

This question was examined in a 2005 environmental assessment report created as part of the Deer Harbor Estuary Habitat Restoration Project, prepared by a consortium of environmental organizations and scientists and funded by the Washington State Salmon Recovery Board.

The study cited land development activities, manipulation of tributary streams, and construction of the Channel Road bridge as reasons for the lagoon’s demise.

“It is believed that these impacts have in turn led to the elimination of shellfish populations in the lagoon, elimination of salmonid rearing and spawning habitat in the tributaries, and degradation of salmonid feeding habitat in the estuary,” reads the report. The study recommended removing blockages in the streams to allow fish passage, replanting the lagoon’s shores to restore shading, controlling erosion, and restoring tidal hydraulics between the lagoon and harbor.

1. Dirty runoff

Runoff from upstream development carries sediment and pollutants into the estuary across the Connor property, which fronts 50 percent of the estuary’s shores. The group’s most recent efforts have focused on mitigating the runoff through creating vegetative buffers, swales and mycological filters. This year Bob Connor and Brown planted 1200 native plants around the estuary, most with “mycelium burritos” (oyster mushroom mycelium wrapped in cardboard) buried at their roots. The plants were covered with wood chips inoculated with turkey-tail mushroom spores, which Ken Brown calls a “complimentary detoxifier.” Brown is currently studying mycology under mycologist Paul Stamets and applying his learning to the restoration work.

The plants draw in runoff, and the mushrooms filter and dissemble petroleum-based waste and microorganisms using biological processes.

2. Dwindling brooks

The estuary drains a watershed of 740 acres. Bubbling streamwater that arrives at the lagoon is almost 100 percent saturated with oxygen, a resource the depleted lagoon badly needs. The problem, Bob said, is that over 80 percent of the expected flow never arrives. As upstream properties have been developed, dams and ponds have been built along the way, allowing water to evaporate or percolate into the soil before it can reach the estuary.

“Our upstream neighbors say they’ll do whatever is necessary to return flow to the stream,” said Bob. “That doesn’t mean people can’t use the water.” He said there are methods of diverting water that don’t disrupt seasonal flow and fish migration routes the way conventional ponds built into the stream sequence often do.

The Connors recently worked with People for Puget Sound to grade the steep entrance to the stream more gently, making it more fish-friendly. But the creek needs more flow before salmon could ascend the stream. A second tributary creek is blocked with a dam, allowing very little flow past.

3. An abbreviated bridge

“No one will admit to [putting in the rock],” said San Juan County engineer John van Lund. A permit map shows that in 1970 a 70-foot span bridge was replaced with a 50-foot span wooden bridge. Roughly 17 feet of rock fill was placed in each side of the lagoon’s mouth, narrowing it significantly.

According to the study, this partly blocked the tidal interchange of oxygen-rich seawater and lagoon water, causing oxygen levels to drop; the rock also prevented tidal scouring, allowing silt to pile up and suffocating bottom-dwelling species like oysters, flatfish and eelgrass. The tide rushing in through the smaller opening also causes greater erosion of the lagoon’s west bank, creating more silt.

“The lagoon has really been affected by this enormously,” Barsh said, adding that if the bridge’s chokehold is not released in time, it could become too late to restore life to the lagoon. “The longer we wait, the poorer the probability of getting the results we want,” he said.

The 2005 study (p.18) said sediment has been piling up in the estuary at a rate of .4 cm per year from the 1860’s; but by their 2005 measurements, .9 to 1.6 cm of sediment accumulated within an 8 month period, seeming to indicate a faster rate of accumulation.

The authors recommended removing 940 cubic yards of rock fill, widening the channel to 85 feet and replacing the current bridge with one spanning 90 feet.

Van Lund said public works is hoping to get 10 more years of life out of the recently repaired bridge, and expects no federal funding for the project.

“The county has no plans to replace the bridge at this time because we’re out of money,” he said. Van Lund also said preliminary calculations indicate that the cost of building an access road around the lagoon would be comparable to replacing the bridge.

Restoration work

“We have a tremendous amount of work to do before we can get fish in that stream again,” said Bob.

Over the years, the Connors have welcomed countless groups of schoolchildren, scientists, college students and environmentalists onto their land to learn and study the ecosystem.

“Though most of the degradation of environmental conditions in our region has been unintentional due to ignorance, we must all be intentional in our restoration efforts,” said Bob.

He said volunteers are welcome to help throughout the spring and summer of 2011 to help with a myriad of tasks, from planting around the estuary, removing invasive species, monitoring water quality and bird species, building swales, installing mycelium and much more.

“We would be happy to take interested groups on a tour of the projects around the estuary on which we are working,” he said. He is in the process of making narrated video/slide shows about the work. Bob also hopes to someday see the establishment of an Estuary Corps that will mobilize volunteers for restoration work.

“I came from an extremely poor, subsistence family,” said Bob. “We knew every plant and fish that we could eat. We did whatever was necessary to survive.” Back then, knowing the local ecology around their hometown of Suquamish kept Bob and his family alive. Nowadays, Bob is doing all he can to spread the word and to mobilize volunteers to breathe life back into Cayou Lagoon.

“I tell people, ‘We can reverse this’. We could change an entire ecosystem,” he said.

The Connors placed seven acres into a conservation easement in 1986 with the San Juan Preservation Trust, establishing the Frank Richardson Wildlife Preserve, home and hotel to over 85 species of migratory and resident birds and many other species of wetland wildlife. They have also placed 70 acres into a conservation easement with the county land bank.

Funding

In 2002 the Salmon Recovery Board granted $139,000 to People for Puget Sound to oversee engineering of a new bridge.

A current grant of $147,000 to People for Puget Sound is earmarked for restorative measures outlined in the 2005 study. Kwiaht is providing third party oversight by inventorying current conditions and wildlife in the lagoon and monitoring the efficacy of restoration efforts funded by the grant.

The estuary is also one of 40 Washington sites being considered for further restoration projects through the Puget Sound Nearshore Ecosystem Restoration Project (PSNRP). The state Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Army Corps of Engineers are currently funding the creation of conceptual designs; after cost-ecosystem benefit analysis, a few sites will receive some funding for restorative measures, which could possibly mean a new lagoon bridge. The projects would theoretically be authorized and funded by Congress through an act like the 2007 Water Resources Development act.